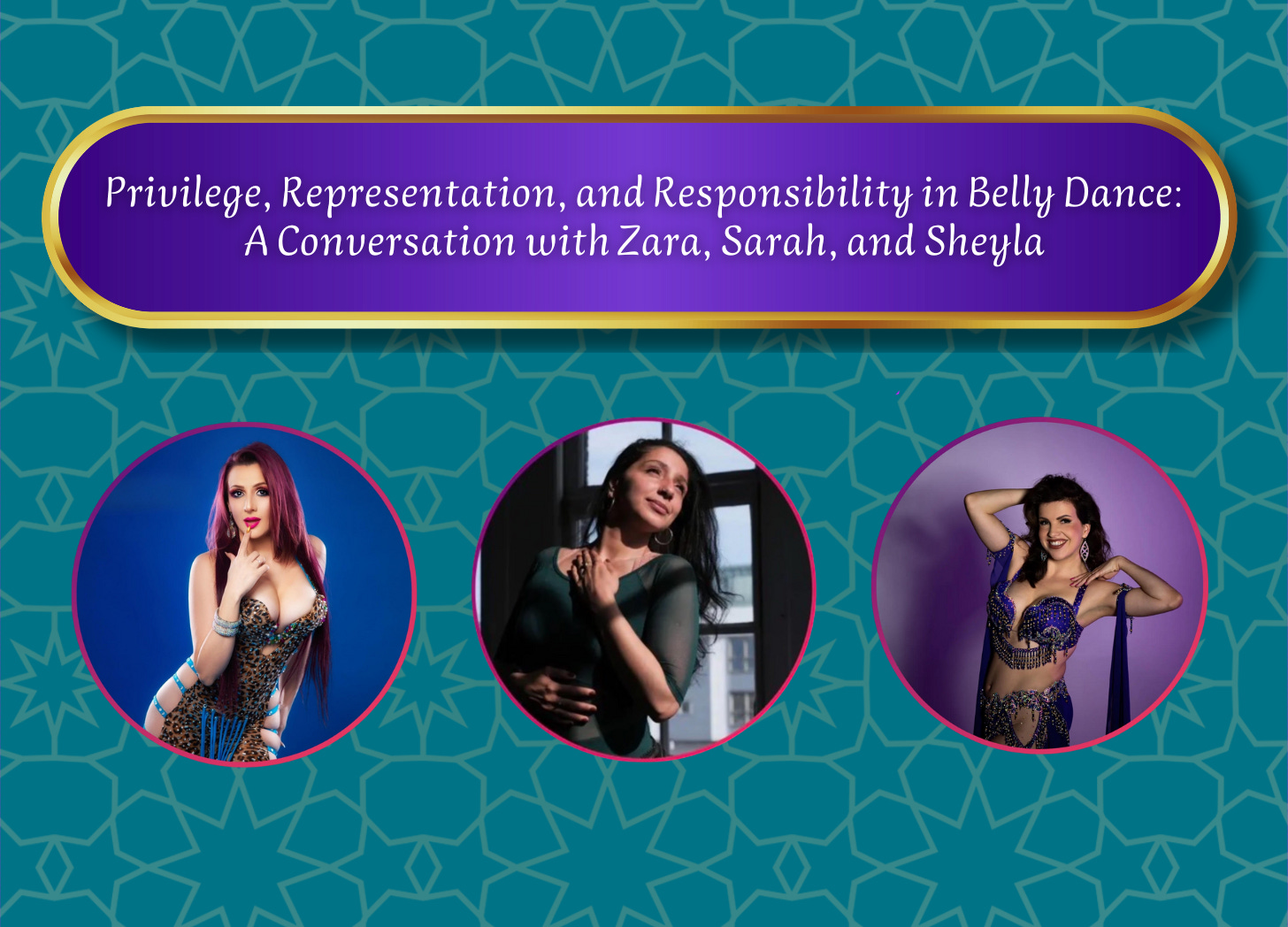

Privilege, Representation, and Responsibility in Belly Dance: A Conversation with Zara, Sarah, and Sheyla

The Al Raqs Conference recently featured a livestream with Zara, Sarah, and Sheyla that opened a rare, direct conversation about some of the biggest topics in this dance that aren’t often addressed on larger stages. They spoke candidly about how privilege shapes access and visibility, why native dancers remain largely absent from major international platforms, and how the economics of the industry influence who receives opportunities and who doesn’t.

Their discussion also acknowledged that Raqs Sharqi holds deep cultural meaning in its homeland, even as it continues to evolve in global contexts. For dancers, teachers, and organizers, this livestream offered a valuable look at the complexities surrounding the art we practice and the responsibilities that come with engaging in it. It was a discussion both heated and heartfelt — a reminder that dance is not only art, but also politics, history, and identity. This recap highlights key themes from the conversation.

Confronting Privilege

The conversation began with a recurring tension many dancers face: the question of whether non-MENAHT (Middle Eastern, North African, Hellenic, Turkish) dancers should perform Raqs Sharqi at all. Sheyla asked what many non-Menaht dancers come across:

“So I cannot dance because I’m not from the culture? I often hear it. And it’s good to confront ourselves. And it’s a good question and good thing to think about...”

Sarah explained that her frustration grew after seeing festival lineups dominated by non-Menaht dancers:

“I think this dance is maybe the least danced professionally by its people ever. The thing is, even though it was a big challenge to be able to do this dance, it was a big fight. I’m extremely privileged because I have a European passport. And this moment that you have privilege, it’s a moment when you have something that’s an immense blessing, and it’s also an immense responsibility.”

While acknowledging the difficulties of being a source (of the culture) dancer, Sarah pointed out the privileges she has as someone with a European passport, positioning herself as a bridge between her community and the international scene.

Zara’s Perspective: Scratching the Surface

Zara agreed with Sarah’s observations but urged everyone to look deeper at the root causes:

“The issues go far beyond just what’s going on in the international market. And I’m very sad to say that a lot of the source issues you are looking at are issues that are further down the line. A lot of the source issues, unfortunately, I’m ashamed to say, are coming from Egypt itself.”

She explained how economic forces and systemic issues in Egypt contribute to the lack of opportunities for Egyptian women to dance professionally:

“When you go to Egypt and you can’t even find Egyptian women dancing in Egypt… then what has belly dance become? The dance has gone, ultimately gone, as a stage art form.”

For Zara, this was not simply about representation abroad, but about survival of the art form in its homeland. She linked the problem to money, entitlement, and systemic structures that incentivize foreign dancers over Egyptian women.

The Call for Change

Both Sarah and Zara insisted that the solution is not about exclusion, but about acknowledging privilege and actively supporting source dancers. Sarah emphasized:

“We’re not saying ‘don’t dance.’ We’re saying give more space. It’s not exclusion, it’s support. Every little thing we do already makes a difference. We’re not demanding everything to change — we’re planting seeds.”

Zara added a more systemic critique:

“We need incentive change, and money is what’s driving this. If you are on the opposite side, if you want change, are you willing to fly out to go to a festival hosted by a source dancer? Because I see a lot of talk, but not as much action.”

Zara’s Call for Nuance

Zara stepped in to emphasize nuance and balance. She reminded listeners that while criticism is necessary, the conversation should not collapse into blame:

“We can talk about privilege and imbalance, but we must also look at the structures behind it. The goal is not to divide dancers of the culture and non-dancers of the culture. The goal is to create awareness and responsibility.”

She echoed the importance of empathy in dialogue:

“If we stay in anger and resentment, nothing will change. We need to see the bigger picture — who is funding, who is validating, and how do we shift that?”

Economics, Validation, and Entitlement

The conversation repeatedly circled back to money as a driver of inequity. Zara explained how foreign dancers’ investments in Egyptian teachers, competitions, and festivals create cycles of entitlement:

“Of course they feel a sense of entitlement. They’ve invested, they’ve been validated, they’ve won a competition. But what they don’t see is that this is happening at the cost of Egyptian women who no longer have space to dance in their own country.”

A Heated Yet Hopeful Dialogue

While the livestream was charged with emotion, it was also grounded in empathy. Zara reminded everyone:

“There’s no point in us being enemies. I love so much of the Western belly dance community — they gave me my whole career. But we need to take the rose-tinted glasses off and see the reality.”

Sarah, too, emphasized love and responsibility, not exclusion, as the core of her message.

“If you’re doing it and making a living from it — the culture is giving you so much. Then it’s the bare minimum to give something back. Peace and love happens when the playing field is leveled. Then peace and love, we can have peace and love.”

Reflection: How Non-Native Dancers Can Be Allies

The conversation naturally leads to a bigger question: What can non-native dancers do to support and stand with source dancers? Here are some reflections drawn from the conversation:

Acknowledge Privilege

Don’t deny it, don’t feel guilty about it — but recognize it. As Sarah said: “It’s okay, dance it. But acknowledge your privilege.”Support Native Dancers with Action, Not Just Words

Invest in festivals, workshops, and projects led by Arab and Egyptian dancers. As Zara reminded us: “I see a lot of talk, but not as much action.”Question Validation Systems

Ask yourself: Who gave me this certificate, award, or contract? Did it come from a system that sidelines Egyptian women?Avoid Romanticizing Access

Performing in Cairo doesn’t automatically equal legitimacy. Challenge the “rose-tinted glasses” effect.Use Your Platform to Amplify Voices

Share the work, perspectives, and artistry of source dancers. Act as a bridge, not a substitute.Approach with Empathy, Not Defensiveness

When issues of privilege come up, resist the urge to feel attacked. Instead, listen and reflect.

Conclusion

The livestream with Zara, Sarah, and Sheyla offered a thoughtful look at the layered realities shaping belly dance today. Questions around access, privilege, and responsibility don’t come with simple answers, yet they continue to shape our classrooms, our stages, and our shared community. Conversations like this help us step past familiar talking points and look more closely at the structures and histories that influence the dance we practice.

Learn more about the work Al Raqs is doing ahead of its January 2026 conference: www.alraqsconference.com.

"Resist the urge to feel attacked" is SUCH an important part of the work.